Geraldene Blackgoat

Ya’at’eeh! I am Geraldene Blackgoat. I am of the Bitter Water Clan and born for the Charcoal Streaked Division of the Red Running into the Water Clan. My maternal grandfather is of the Water’s Edge Clan and my paternal grandfather is of the Black Sheep Clan. I am originally from Sanders, Arizona, which is at the southern edge of the Navajo Nation, approximately thirty-five miles west of Gallup, along Interstate 40.

Ya’at’eeh! I am Geraldene Blackgoat. I am of the Bitter Water Clan and born for the Charcoal Streaked Division of the Red Running into the Water Clan. My maternal grandfather is of the Water’s Edge Clan and my paternal grandfather is of the Black Sheep Clan. I am originally from Sanders, Arizona, which is at the southern edge of the Navajo Nation, approximately thirty-five miles west of Gallup, along Interstate 40.

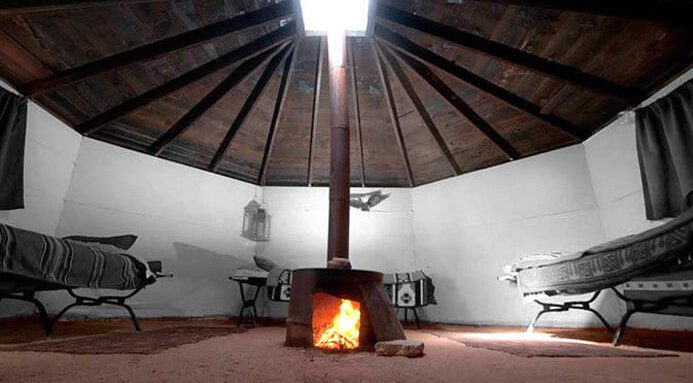

While growing up on the Navajo Nation, my mother kept my siblings and me close to our cultural traditions, especially the ceremonies. There are various types of ceremonies that are practiced to bring healing, balance, and wellbeing—Hózhó—to individuals and families. The larger and more specialized ceremonies are meant to be held in a hogan, as our ancestors practiced. Our deities connect with us during our ceremonies. I learned the importance of these at a young age; however, I also noticed inconsistencies in where ceremonies were held. There were times we had small ceremonies in our home, which was provided by the Navajo Housing Authority (NHA), the tribally designated housing entity of the Navajo people. For overnight ceremonies, we went to my grandmother’s house on a rural ten acres that contained her house, hogan, livestock, and cornfield. The hogan’s door opens to the east. The floor is earth, a wood stove is in the very center, and the chimney is elongated through the apex, held with wires, leaving some of the sky exposed. Each of these aspects plays a critical role in Navajo ceremonies, none of which exist in my family’s NHA home. Our home is a south-facing, rectangular stick-frame house with a gable roof and a yard of less than half an acre. It is this disconnect that pushed me toward studying architecture.

Our homes and land should support our cultural practices, whether it be ceremonies, family gatherings, planting of crops, or raising livestock.

I attended the University of New Mexico School of Architecture and Planning for my undergraduate and graduate degrees. I currently work at Greer Stafford/SJCF Architecture in Albuquerque, where I am gaining a deeper understanding of the technical side of architecture and design—a crucial part of my journey to becoming a licensed architect. As a Navajo woman pursuing this professional stature, I am inspired by Native American and First Nations women architects—though there are fewer than ten Native American women architects in the United States (among them, one other from the Navajo Nation). I am truly humbled to have worked with and met most of these women.

I recall being in high school and wondering if Native American architects existed. I searched online and found maybe one or two names. It was inspiring to see that they were out there—even if it was only men. Yet it was discouraging to learn that there were so few. During undergraduate school, I was finally exposed to Native architects, specifically Navajo architects. Even more exciting was taking a class and eventually working under the only Navajo woman architect, Tamarah Begay. There were only a handful of Native students in the architecture and planning programs, and seven of us were active members of the American Indian Council of Architects & Engineers (AICAE) student organization. My first AICAE annual conference was in Albuquerque, where I met the professional members of the organization, which include architects, engineers, landscape architects, interior designers, planners, and educators from all over the country. I was in awe, and I was in my element!

Our ancestors were strong and resilient because of our culture, traditions, and language.

Throughout my career, the fundamental questions I had as a kid have been pushed further. During graduate school, I opted to complete a master’s project focused on how families practice their ceremonial rituals in NHA homes. With an amazing committee, I developed “Navajo Ritual Spaces in Housing,” a thesis that illustrates ways to improve the design of homes for Navajo families concerning ceremonial rituals. I interviewed four families who live in two different NHA housing developments in my hometown. Interviews were also conducted with three medicine men (Navajo shaman/healers), who have led various ceremonies in many types of homes throughout the Navajo Nation. Each family described how they adapt their NHA homes to the spatial requirements of ceremonies. Most of the families lacked open space in their living room, so they would rearrange or relocate their furniture to make sufficient room for everyone to sit on the floor, for example. Kitchens were also near the top of the list in terms of insufficient space, because there could not be more than two or three persons in the kitchen at a time preparing food for large groups. The families and medicine men adapt the spaces they’re provided to conduct ceremonies but agree that more consideration should be given to the design of the homes, both the interior and exterior. Our homes and land should support our cultural practices, whether it be ceremonies, family gatherings, planting of crops, or raising livestock. Another topic of discussion during my research was about access to community hogans in NHA developments, allowing for any family to use them, as opposed to trying to accommodate ceremonies in their own houses. Most families who live in NHA homes do not have hogans due to the cost, insufficient space in their yards, or because there are restrictions on building additional structures. I question how all of this has already affected—and continues to affect—our culture.

Photo: Facerock Productions.

There are over six hundred federally recognized tribes in the U.S., each with distinct cultures, traditions, languages, and landscapes, so it makes sense that our architecture reflects and accommodates these unique needs. During this journey, I want to inspire other Native kids to question their surroundings and work towards improving and reclaiming our cultures in sensible ways. Our ancestors were strong and resilient because of our culture, traditions, and language. We should advocate to preserve and reclaim all that we can with the goal of Hózhó for ourselves, our people, and future generations. I am thankful to those who are tirelessly making it a reality in their respective fields. I see you!

Geraldene Blackgoat, AICAE, Assoc. AIA, is Bitter Water Clan, born for Charcoal Streaked Division of the Red Running into the Water Clan. Geraldene is a first-generation college graduate who found inspiration in her upbringing to pursue architecture. Her background is in architectural design, culturally appropriate design, community participatory research, and college outreach to Native American students. She is an adjunct lecturer at UNM School of Architecture and Planning and an intern architect in Albuquerque.

Michaela Shirley

A revelation came in a moment of idleness as I stood upon a mountain behind the herd of sheep who were grazing upwards toward the power lines, because we needed to water them that day. It was a warm mid-70s sunny day with sparse clouds in the blue sky above and tall pine trees all around, embracing me, while the smell of moist, cool dirt evaporated up my nose. Big boulders were buried in the slopes of the mountain as if they were playing hide-and-seek with me, and pebbles tickled me as I walked. The warm winds going through the oak and pine trees were like whispers in my ears. The sheep’s bells (used so we could hear the herd wherever they went) sounded in the distance, as they slowly grazed up the mountainside, my niece to the right of the herd and my Nali Isabelle to the left. Each of us was in tranquil stance. Who knows what they were thinking in their moment of contemplation, because when we herd the sheep, there’s no talking. There’s only you, alone in your thoughts, whatever they are, however they come to you.

A revelation came in a moment of idleness as I stood upon a mountain behind the herd of sheep who were grazing upwards toward the power lines, because we needed to water them that day. It was a warm mid-70s sunny day with sparse clouds in the blue sky above and tall pine trees all around, embracing me, while the smell of moist, cool dirt evaporated up my nose. Big boulders were buried in the slopes of the mountain as if they were playing hide-and-seek with me, and pebbles tickled me as I walked. The warm winds going through the oak and pine trees were like whispers in my ears. The sheep’s bells (used so we could hear the herd wherever they went) sounded in the distance, as they slowly grazed up the mountainside, my niece to the right of the herd and my Nali Isabelle to the left. Each of us was in tranquil stance. Who knows what they were thinking in their moment of contemplation, because when we herd the sheep, there’s no talking. There’s only you, alone in your thoughts, whatever they are, however they come to you.

If not the mountain, then it was certainly the spirit of my ancestors that uttered sweetly to me that this is the most important thing, that this is what I needed to protect for future generations.

Since the fourth grade, I wanted to go to college. It was something I kept in the back of my mind. While contemplating what career would be my life’s work, I knew that the field I chose—or, rather, the field that was going to choose me—would be one that enabled me to help my community. Spending the summers with my Nali Isabelle Shirley was a crucial time in my life. The four summers I spent at her sheep camps in the mountains were when the mountain gave me my most cherished gift: the mountain gifted me a moment in time that informed my purpose in life. “What is going to be the career that is going to help me protect this?” I asked myself. “This… what I’m staring at, this that is embracing me, this which has been given to me by the mountain?” The mountains where I spent my summers at sheep camp are the same mountains where generations of people before me have lived. The mountain knows me through my family’s lineage. If not the mountain, then it was certainly the spirit of my ancestors that uttered sweetly to me that this is the most important thing, that this is what I needed to protect for future generations. It is as my parents, Paul and Dolly Shirley, say: “Breathe in the mountains; you belong to the mountains.” There is no telling for sure how I came into this conviction, but I am thankful for it. Whenever I run into challenges in my work or when I start to encounter self-doubt while exploring how our Indigenous communities can be stronger, I go back to this moment, because it was one of the defining instances in my life.

My name is Michaela Paulette Shirley. I am Water Edge People clan, born for Bitter Water clan; my maternal clan is Salt People and my paternal clan is Coyote Pass. I am originally from Kin Dah Lichii, located in northeastern Arizona in the Navajo Nation. My life pursuit of broadening and building the scholarship of Indigenous planning began with Dr. Ted Jojola in my undergraduate urban planning program at Arizona State University. His guidance continued in my master’s degree program in community and regional planning at the University of New Mexico. Now, I mentor others in my staff position as program specialist with the Indigenous Design and Planning Institute at UNM’s School of Architecture and Planning. My purpose as an Indigenous planner is to be a lifelong learner of my own culture and to explore my identity as a Diné woman. In my work, I inform tribal communities’ development in respect to their cultures and identities.

Indigenous planning is a field of study and practice that encourages Indigenous communities to develop culturally appropriate plans and designs, using their traditional values. As I become stronger in the foundation of these aspects of my own identity, I reflect on the concept of Hózhó and its role in advancing my Indigenous planning theoretical framework as an emerging scholar and practitioner. My Diné-centered Indigenous planning framework of Hózhó is seven levels of beauty that span the lifetime of a Diné person. The seven levels of beauty correspond to our Beauty Way prayer. Beauty is the songs sung and prayers said that have folded into hope, love, faith, and resilience by ancestor matriarchs. Beauty is living a full life—a full life in the sense that the force of life is strong and contributes to resilient Indigenous communities. Hózhó is all aspects of the person’s spirit, emotions, and physical presence that is in rhythm with the community’s spirit, emotions, and built and natural environments.

Beauty is the songs sung and prayers said that have folded into hope, love, faith, and resilience by ancestor matriarchs.

Today, there is a disconnect between individuals and the community because we no longer know how to be in sync with Hózhó, a synchronicity that is kind, loving, and respectful. The Hózhó framework ensures that everyone has a role and responsibility to serve and bestow their gifts within the community. Syncing and ascending levels of Hózhó means having coherence with one’s purpose in life. Corn is an important symbol to illustrate Hózhó, because corn nourishes people and provides pollen for prayers and ceremonies. In order to climb the various levels of Beauty to achieve Hózhó, I must recognize and honor the matriarchs (the past), whose lives my life is sprouting from. From there, my identity, culture, and values as a Diné woman are rooted as I grow into a strong stalk (the present). Once the different levels of Beauty have been attained, I will be the Beauty. At the peak of Hózhó, I am ready to share Beauty with the rest of my community in the role I was born into (the future).

It is remarkable how far we, the Diné, have come, and I am hopeful for our future. What does the future mean to me as an Indigenous planner? I often ponder my role and my responsibility to create with others compelling and meaningful planning strategies for the generations to come. There are incredible peers of mine, like Geraldene Blackgoat, Cheri Lynn Devore, Tamarah Begay, Danielle Begay, Jana Pfeiffer, Michelle Pfeiffer, Lani Tsinnajinnie, and Kim Kanuho, who are diligently ascending in Hózhó, individually and collectively. They make me proud of who we are and show what we are capable of, because we’ve always been in this ascendance. We need to take time to reflect and pray on what has been done and work with what we have to fill the gaps. All this requires countless discussions in our homes, community meetings, schools, ceremonies, and on long drives across our homelands. Indigenous planning secures and enhances our sovereignty. Are you ready to dream and work hard with me?

Michaela Shirley, MRCP, (Diné), is Water Edge clan, born for Bitter Water clan, and her grandfathers are Salt and Coyote Pass clans. Michaela’s background is in urban planning, community development, and Indigenous planning, with research interests in Indigenous historiography, community-school relationship, youth engagement/development, biographies of landscape, and Diné studies. She is a current PhD student in the UNM American studies program. Michaela is a program specialist for the Indigenous Design and Planning Institute at UNM.